Why A&E is struggling to be a ‘place of safety’ for mental health patients in crisis

Waiting times for people with a mental health problem attending one of our A&E departments are steadily rising. Like most acute NHS trusts, we don’t provide mental health services directly. Instead, we work with our local mental health NHS trusts to ensure mental health patients get the specialist care they need to meet their needs. As episode three of Hospital demonstrates, prolonged waits to access inpatient mental health beds for A&E patients are having a big impact on patients and staff. Here Claire Braithwaite, our director of operations for the division of medicine and integrated care, explains why A&E departments struggle to be a ‘place of safety’ for mental health patients in crisis and how a ‘whole system’ approach is the only long-term solution.

Though we don’t provide specialist mental health services, our two A&E departments are increasingly acting as a safety net for people with urgent mental health problems or whose on-going care and support breaks down. Also, an increasing number of patients are presenting with complex health and care needs that can take time to unravel.

One reason why A&E departments are playing a bigger role in the care of mental health patients was triggered by a new code of practice published in 2015. If a person needs to be detained under section 136 of the Mental Health Act – generally known as being ‘sectioned’ – they have to be moved to a ‘place of safety’ to be assessed.

The new code of practice said that police stations should no longer be used as places of safety unless there were exceptional circumstances. In practice, psychiatric units or hospital A&E departments are most commonly used. The Healthy London Partnership – made up of statutory bodies working across health and social care – say that 75 per cent of section 136 detentions occur out of hours, yet the majority of specialist sites do not have dedicated staffing for 24 hours a day, seven days a week.

In north west London, there are six ‘section 136 suites’ operating 24/7, run by specialist mental health NHS trusts. Mental health patients are also brought in to A&E, often because they have an urgent physical health problem too, but not always.

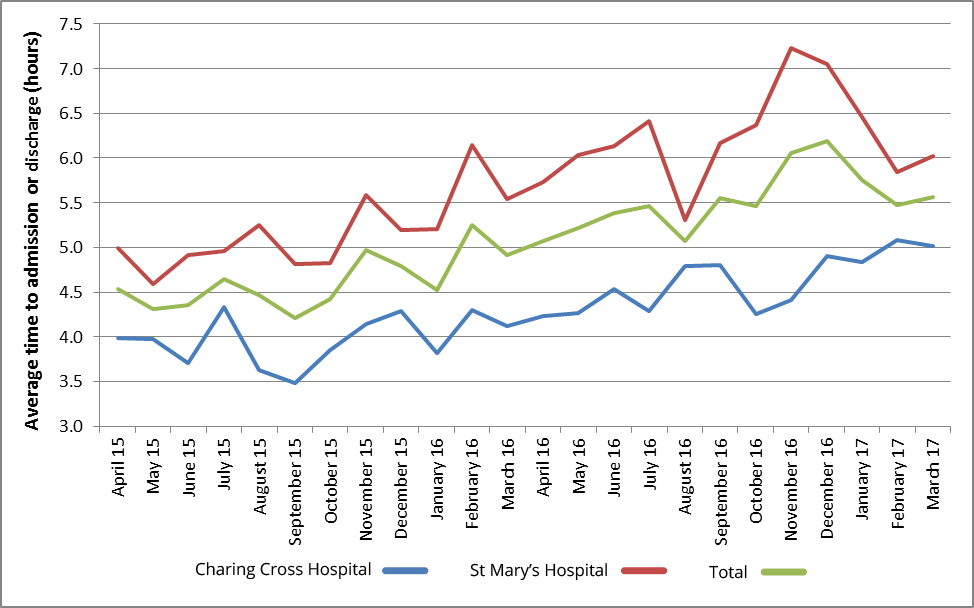

The graph below shows the average length of time that patients with a mental health complaint attending our A&Es waited from the time of arrival to admission or discharge. This continues to rise and has increased from 4.6 hours on average in 2015/16 to 5.5 hours in 2016/17.

As with all A&E attendances, the national standard is for 95 per cent of patients to be assessed and admitted or treated and discharged within four hours of arrival. In 2015/16, this standard was met for 65 per cent of patients with a mental health related complaint. This decreased to 56 per cent in 2016/17.

Both of our A&Es have access to a mental health liaison service. These services are commissioned directly by the local clinical commissioning groups and are provided by our partners, Central and North West London NHS Foundation Trust at St Mary’s and by West London Mental Health NHS Trust at Charing Cross. While the majority of patients are seen within one hour of referral to the psychiatric liaison team on both sites, delays often arise in organising the next step in care following initial assessment. The problem is especially acute for patients under the age of 18 who require access to specialist child and adolescent mental health services.

Patients who require admission to a mental health bed experience the longest waits for treatment. In February 2016, we reported our first 12-hour A&E ‘trolley wait breach’ in recent history. A breach happens when a patient waits over 12 hours from the time a decision is made that they require admission to their transfer to an inpatient bed. The patient was waiting for a mental health bed. Between then and March 2017, there have been a further 26 12-hour trolley wait breaches.

As you see in Hospital, our A&E departments do provide a place of safety for mental health patients – but it is not as safe or as suitable as it should be. A busy, often noisy and sometimes crowded A&E is not a good environment for any patient for extended periods of time, not least for someone with a mental health problem. Some mental health patients will be confused or aggressive – this is a risk for other patients and our staff as well as for the patient themselves.

We’re working hard, internally and in partnership with local commissioners and mental health providers, to improve the service for mental health patients attending A&E.

In the short term, we have agreed new processes for A&E staff to escalate long waits to senior managers, commissioners and partner trusts so that additional support can be given to help find more suitable care. We now report all 12-hour trolley wait breaches as serious incidents to help build up a full picture of the problem and root causes. We are also employing more registered mental health nurses ourselves in A&E so that patients have specialist care while they are waiting.

We have an increased focus on preventing violence and aggression across our Trust. Obviously, for some patients with mental health problems or impairments, the approach has to be about ensuring we carry out effective risk assessments and match needs with the right staffing – one of the reasons why we have increased our direct employment of mental health nurses. It’s also important to have the right training, support and security in place.

Longer term, we have to have a more joined up approach to health and care. One of our key developments is an initiative currently focusing on Hammersmith and Fulham. We are working in partnership with local GPs and other NHS providers, including West London Mental Health NHS Trust, and linking in with the local authority and clinical commissioning group, to explore a new model of care. We are looking to pool the resources we spend on the population collectively to redesign care pathways around patients’ needs rather than around our organisational remits. Ultimately, we hope this will enable us to target resources to provide care when and where the patient needs it. Our physical health, mental health and social care needs are intertwined – we need services that are organised in the same way.